and We’re Back

That pause wasn’t a retreat. It was a reset

“Once we realize that imperfect understanding is the human condition, there is no shame in being wrong, only in failing to correct our mistakes.” — George Soros, Soros on Soros: Staying Ahead of the Curve (1995)

In October, I took the desk dark. Not because I ran out of things to say, but because I couldn’t say them well enough to justify your attention. The day job, the personal constraints, the reality that institutional-grade work doesn’t survive on borrowed hours—something had to give. I choose silence over slippage.

That pause wasn’t a retreat. It was a reset.

I told you January would bring something different, but I couldn’t keep you waiting. More structured. More consistent. Built for the long run rather than patched together around everything else. This is me making good on that. I just gave you some recommendations within my playlist with a small tweak into one of the classics in 90s music culture. Feel free to listen while reading the rest of the article, or wait till the end to match the fire.

I used to run a Full Metal Jacket-type publication schedule—basically trying to push out two to three articles per week. But as some of you may have noticed, keeping that pace while juggling personal life and workplace politics is genuinely hard. Anyway, enough complaining about that.

Think of this article as an announcement that I’m back in the arena.

And I’m not alone: Michael Burry “Cassandra” has returned to the playground as a brother in arms (he’s already landed himself on the Top Sellers Leaderboard, no less).

Congratulations to him.

I’ve been thinking: should I explain these publications in more detail, or let the first issues speak for themselves? The second option feels more honest, and my audience deserves that. I’ve left my old articles without any paywalled content—keep that in mind.

As often attributed to Wilson Mizner: “If you steal from one author, it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many, it’s research.” Pablo Picasso said something similar: “Good artists copy; great artists steal.” Many more have made similar statements about “stealing” ideas; however, to borrow others’ ideas, you have to see them, and this means increasing your powers of observation. Are they recognized as thieves or great artists in their own area of expertise? Stealing really means taking something as a starting point, then using your creativity to transform and synthesise it into something new.

As Hemingway said, “It would take a day to list everyone I borrowed ideas from, and it was no new thing for me to learn from everyone I could, living or dead. I learn as much from painters about how to write as I do from writers.” Now let me show you the framework behind what’s coming.

Paradoxes and Uncertainty

For the next structure, I will be using my own MSc thesis topic: paradoxes and their way of explaining things that have uncertainty in their nature.

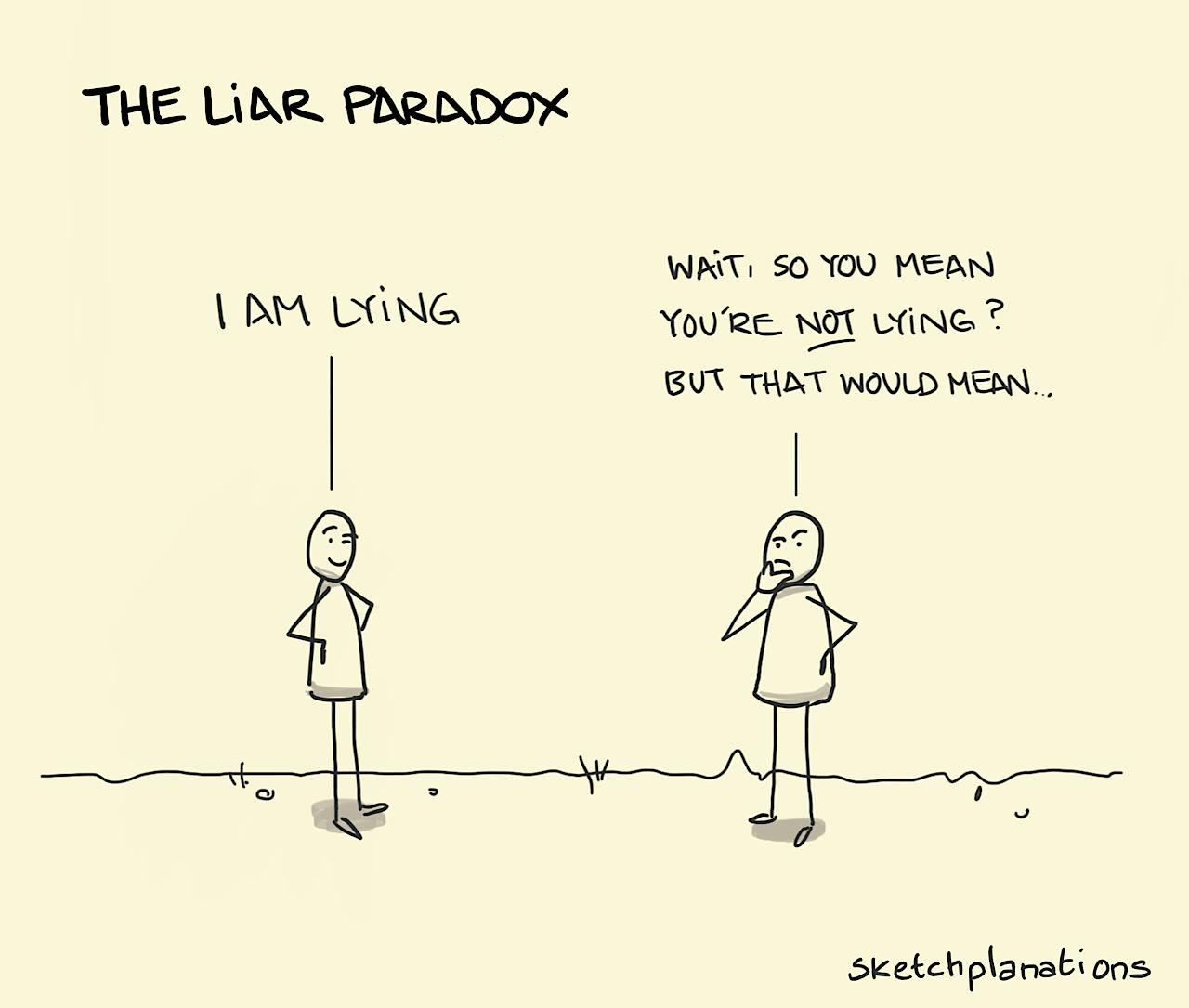

We all know the term paradox, but do we really know its meaning?

Self-reference comes to mind. The Liar’s Paradox—“this sentence is false”—is paradoxical because if the sentence is true, it means it is false, but if it is false, it means it is true. Bertrand Russell resolved the paradox by placing self-referential statements into a separate category and declaring them meaningless.

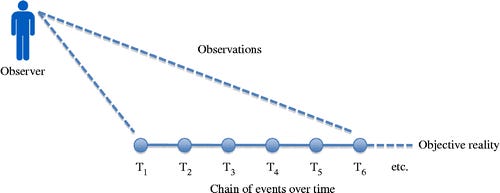

In practice, it is impossible to avoid either self-referential or reflexive statements. Agents cannot acquire all the knowledge they need to make decisions; they must act on imperfect understanding. While their actions can shape the world, outcomes are unlikely to correspond to expectations. There is bound to be some slippage between intentions and actions, and further slippage between actions and outcomes. Since agents base their decisions on limited knowledge, their actions are liable to have unintended consequences.

This means that reflexivity introduces an element of uncertainty both into agents’ view of the world and into the world in which they participate. But reflexive systems are dynamic and unfold over time as the cognitive and manipulative functions perpetually chase each other. Once time is introduced, reflexivity creates indeterminacy and uncertainty rather than paradox.

The Theory of Reflexivity

By now, I believe you understand the meaning of paradoxes and why I find them useful. You may find some correlation through the theory of reflexivity—George Soros’s very own brainchild. It is safe to say that I found quite a bit of inspiration from him. Let me explain in a simplistic way what the theory is about and why you can also use it in your own thinking.

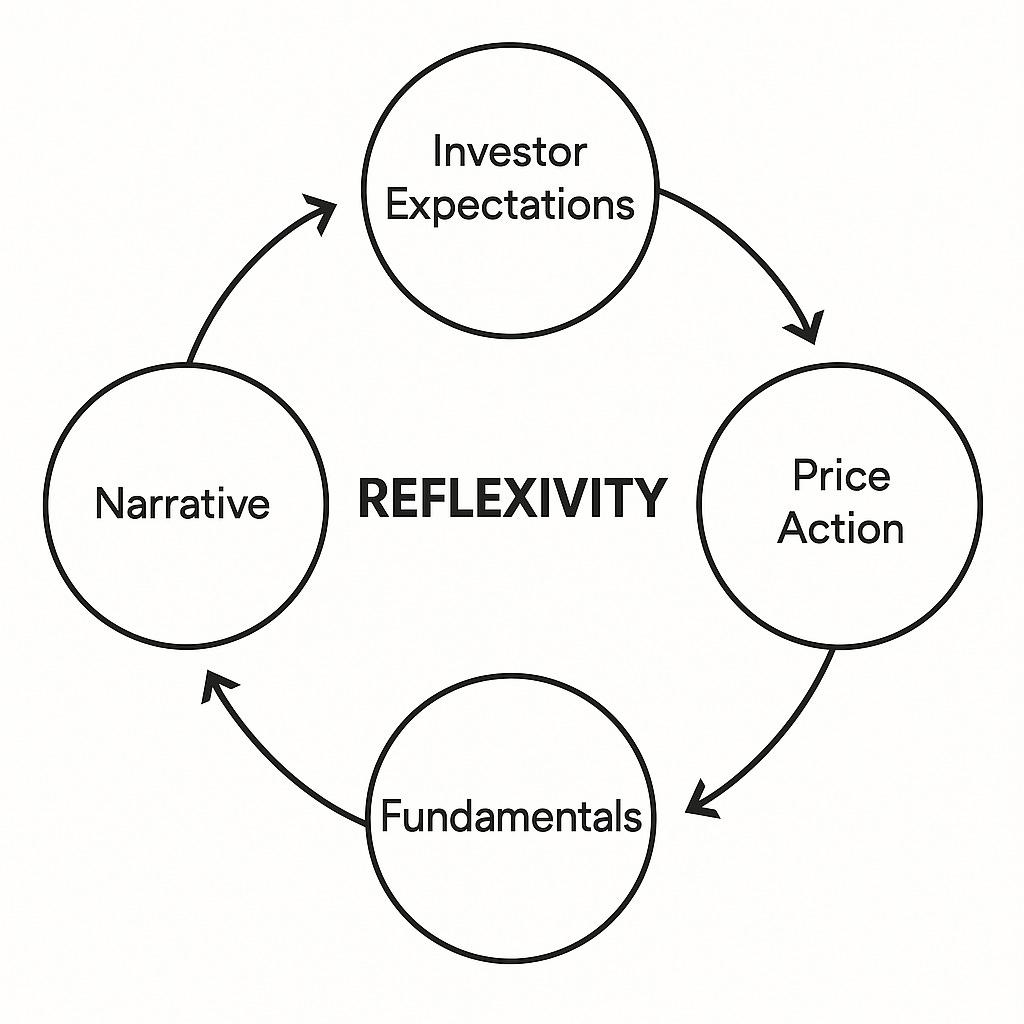

Reflexivity refers to a theory in economics where investors’ perceptions influence economic fundamentals and, in turn, those fundamentals affect market prices. Reflexivity originates in sociology, but with George Soros, it became more prominent in finance. He believes that deviations from economic equilibrium are due to positive feedback loops. According to Soros, reflexivity theory challenges equilibrium and the efficient market hypothesis. The theory states that investors don’t base their decisions on reality, but rather on their perception of reality. The actions that result from these perceptions have an impact on reality, or fundamentals, which then affects investors’ perceptions and thus prices. The process is self-reinforcing and tends towards disequilibrium, causing prices to become increasingly detached from reality.

Soros sees the global financial crisis as an example of this theory. In his interpretation, rising home prices induced banks to increase their home mortgage lending, and in turn, increased lending helped drive up home prices. Unchecked rising prices created a bubble that eventually burst, leading to crisis. His reflexivity theory opposes economic equilibrium, rational expectations, and the efficient market hypothesis.

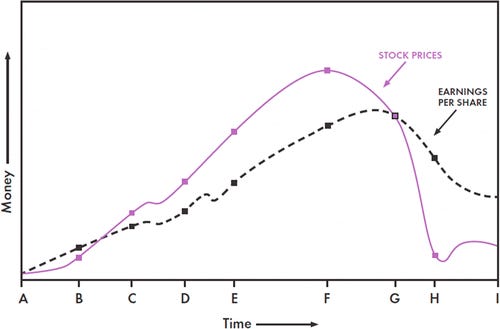

The cycle of a typical market boom–bust works like this: In the initial stage (AB), a new positive earning trend is not yet recognized. Then comes a period of acceleration (BC) when the trend is recognized and reinforced by expectations. A period of testing may intervene when either earnings or expectations waiver (CD). If the positive trend and bias survive the testing, both emerge stronger. Conviction develops and is no longer shaken by a setback in earnings (DE). The gap between expectations and reality becomes wider (EF) until the moment of truth arrives when reality can no longer sustain the exaggerated expectations and the bias is recognized as such (F). A twilight period ensues when people continue to play the game although they no longer believe in it (FG). Eventually, a crossover point (G) is reached when the trend turns down and prices lose their last prop. This leads to a catastrophic downward acceleration (GH) commonly known as the crash. The pessimism becomes overdone, earnings stabilize, and prices recover somewhat (HI).

For more, see George Soros’s The Theory of Reflexivity delivered April 26, 1994, to the MIT Department of Economics World Economy Laboratory Conference.

Traditional Economics vs. Reflexivity

Mainstream traditional economics suggests that real fundamentals, like supply and demand, imply equilibrium prices. Changes in fundamentals, like consumer preferences and scarcity, cause markets to adjust prices based on expectations. This process includes both positive and negative feedback between prices and expectations regarding economic fundamentals, which balance each other out at a new equilibrium price. In the absence of major obstacles to communicating information and engaging in transactions at mutually agreed prices, this process will tend to keep the market moving quickly and efficiently toward equilibrium.

Soros challenges this. He argues that equilibrium prices can deviate significantly due to reflexivity. Price formations are reflexive and driven by feedback loops between prices and expectations. Once a change in economic fundamentals occurs, these positive feedback loops cause prices to undershoot or overshoot the new equilibrium. The normal negative feedback between prices and expectations—which would counterbalance these positive feedback loops—fails.

Eventually, the trend reverses once market participants recognise that prices have become detached from reality and revise their expectations. He uses boom-bust cycles and price bubbles (if you want to learn more about bubbles, feel free to dive into the Chicago Fed’s Letter published by Douglas D. Evanoff, George Kaufman, and Anastasios G. Malliaris: Asset Price Bubbles: What are the Causes, Consequences, and Public Policy Options?), followed by crashes, to support his theory. These episodes show prices straying from equilibrium, with leverage and credit availability initiating the process, alongside the role of floating foreign exchange rates.

Friedrich Hayek and the Denationalisation of Money

I also found quite a bit of inspiration from Friedrich Hayek. Back in 2020, reading his essay “The Denationalisation of Money” inspired me to buy my first cryptocurrency as an experiment.

Hayek advocated for the establishment of competitively issued private moneys. He speculated that rather than tolerating an unmanageable number of currencies, markets would converge on one or only a limited number of monetary standards, on which institutions would base the issue of their notes.

According to Hayek, instead of a national government issuing a specific currency—the use of which is imposed on all members of its economy by force in the form of legal tender laws—businesses should be allowed to issue their own forms of money, deciding how to do so on their own. Hayek advocates a system of private currency in which financial institutions create currencies that compete for acceptance.

Stability in value is presumed to be the decisive factor for acceptance. Hayek assumes that competition will favour currencies with the greatest stability in value, since a devalued currency hurts creditors and an upward-revalued currency hurts debtors. Hence, users would choose monies that offer a mutually acceptable balance between depreciation and appreciation.

Hayek suggests that institutions may find through experimentation that an extensive basket of commodities forms the ideal monetary base. Institutions would issue and regulate their currency primarily through loan-making, and secondarily through currency buying and selling activities. It is postulated that the financial press would report daily information on whether institutions are managing their currencies within a previously defined tolerance.

Hayek’s effort has been cited by economists George Selgin, Richard Timberlake, and Lawrence White. According to the European Central Bank, the decentralisation of money offered by Bitcoin has its theoretical roots in The Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined. However, political philosopher Adam James Tebble has argued that there are important differences between Hayek’s vision and cryptocurrency, because the latter takes decentralisation a step further than Hayek ever envisaged.

Intellectual Lineage

I believe that would be a good way to explain my mindset and the pioneers who helped me find my unique voice without going into much detail. Of course, George Soros was not the person who discovered reflexivity; early observers recognised it, often under different names:

Frank Knight (1921) explained the difference between risk and uncertainty.

John Maynard Keynes (1937) compared financial markets to a beauty contest where participants had to guess who would be the most popular choice.

Robert K. Merton (1949) wrote about self-fulfilling prophecies, unintended consequences, and the bandwagon effect.

Karl Popper (1957) spoke about the “Oedipus effect”—the influence of a prediction upon the event predicted.

I won’t be the first person to write about these topics on my Substack, nor will I be the last, but I can assure you that it will be worth every minute of your precious time.

I also strongly recommend watching Soros’s lecture series from 2010 at the Central European University:

Conclusion

I hope you now understand the intellectual framework that will guide my future work. The thinkers I’ve introduced—Soros, Hayek, Knight, Keynes, Merton, Popper, and many more—have all shaped how I approach uncertainty, market dynamics, and the complex feedback loops that govern our financial systems. These ideas are not merely academic exercises; they are practical lenses through which we can interpret the world around us and make more informed decisions.

The core message here is simple yet profound: we operate in a world defined by imperfect knowledge and reflexive relationships. Our perceptions shape reality, and reality, in turn, reshapes our perceptions. This interplay between cognition and action creates the uncertainty and indeterminacy that traditional economic models often fail to capture. By embracing this complexity rather than ignoring it, we position ourselves to navigate markets and life with greater clarity and humility. The new structure will reflect a more realistic approach.

Going forward, I am committed to diving deep into academic articles, industry reports, research papers, and news sources—both traditional and modern—to uncover what others may overlook or ignore. My goal is not to predict the future with certainty, but rather to illuminate the patterns, biases, and feedback mechanisms that drive outcomes in ways we often fail to recognise.

To that end, I am excited to announce my two new publications:

Finding Goya will be published every week and will focus on timely analysis, market observations, and the application of reflexive thinking to current events.

Red Boy Whispers will be published monthly and will take a deeper, more contemplative approach—exploring broader themes, longer-term trends, and the philosophical underpinnings of the ideas I’ve discussed today.

The mechanics haven’t changed. If you were subscribed before the pause, billing resumes now. If you dropped off and want back in, the door’s open.

Thank you for joining me on this journey. I am genuinely grateful for your time, your attention, and your willingness to engage with these ideas.

Views and opinions expressed herein are exclusively my own.

Have a good evening.

— Riko

Welcome back, Riko. I loved your beautiful stock prices relative to earnings per share chart, so I stole it, and will educate my readers with it. Full credit to you, of course.